As a podcast evangelist, I’m happy to announce that a couple of my articles are now available for your iPod pleasure at industrybroadcast.com.

As a podcast evangelist, I’m happy to announce that a couple of my articles are now available for your iPod pleasure at industrybroadcast.com.

The Power of Weakness 4: Some preliminary definitions

So Jonas, what is this “power of weakness” thing you keep going on about? you, the implied reader, ask.

So Jonas, what is this “power of weakness” thing you keep going on about? you, the implied reader, ask.

And I want to thank you for taking the time, because that is a truly relevant inquiry.

The whole thing revolves around something which I find fascinating: That, in many diverse situations, we go out of our way to inhibit ourselves. We set up our environment in ways which limit us from making certain choices in the future. And we do so intentionally in order to gain an advantage.

The phenomenon is curious, since intuitively more options is better. In practice this is often not the case and examples are easy to come by: The dieter cleans out the fridge to eliminate temptations, the would-be cigarette quitter makes sure that the house is cigarette free, the writer shuts down his internet browser to avoid the temptation of checking online newspapers.

In these examples, a person fears that his future self will not share his current preferences. The current you prefers not having a chocolate bar to having one, but you fear that the person you will be in an hour will feel differently. In a sense, you’re engaged in a conflict with your future self.

Notably, this is different from merely fearing that your future self will not remember that which you presently have in mind. You’re acutely aware that you’re out of milk, but you fear that your future self (faced with the distractions of a thousand special supermarket offers) will (once again) forget to buy a certain dairy product. So you influence the cognitive focus of your future self by that powerful technique: The shopping list. This is not an example of the power of weakness, since your future self is not restrained, merely reminded of what he actually wants to do.

The power of weakness is not, however, limited to your battles with your fickle future self. Yes, I’m referring to the mass of mobile shapes commonly referred to as “other people”. At times, you want to limit your future options in order to elicit a particular response from someone else. This is something I’ll come back to ad nauseam, but a banal example is the commonly used strategy used whenever two people engage in that little left-or-right dance in which they need to move past each other without collision: To visibly commit to one side and avert one’s eyes (thus limiting one’s options as of this very moment). The message is this: We have no obvious way of solving this coordination problem and it doesn’t actually matter (i.e. no-one wins and loses) who does what, so I’ll simply choose left now thank you very much.

So, the power of weakness is: The phenomenon that, in certain situations, limiting one’s future options bestows a personal advantage.

Stay tuned for burning ships, suicidal drivers, kidnappers, speech acts, and bee wax.

The Power of Weakness 3: Norwegian News Flash

Image 1: Trond Giske, Norwegian minister of culture

Technically we’re off topic here (unless our topic is very broad indeed) but I just realized that the near-Danes of Norway have taken a drastic approach to the lure of gaming.

Distressed with the rise of gambling addiction, the Norwegian government last year chose to ban all privately owned gambling machines. Lest riots should appear, the government is rolling out strictly controlled tailor-made machines which uphold a strict time and money limit and which are intentionally free of all the bells and whistles which normally attract gamers/gamblers.

Now, this is not directly related to the power of weakness, but a government is arguably a group’s way of controlling itself by adjusting the attraction of certain actions. I’ll get back to that in a later post. Right now I just thought that this was interestingly drastic and game-related to boot.

More details from Associated Press and for pictures of the unattractive wonder see VG.

The Power of Weakness 2: Lead me not into instant messaging

Working the way I usually do – backed up powerfully by Wikipedia, Google; seriously revising drafts etc. – I sometimes wonder how on Earth pre-computer people were able to do any serious writing.

Of course, I also – paradoxically – sometimes wonder if I wouldn’t be able to work faster, better and with far greater personal gratification if it was just me and a clunky old type-writer alone in a secluded cabin deep in some Swedish forest.

I suppose most of us feel that way. Distractions and how to manage them is certainly a prevalent topic on blogs such as Lifehacker (offering tips on all aspects of your digital existence). Witness also the rise of no-nonsense retro-style full-screen word processors such as Writeroom and Dark Room. These offer to limit your options, for a price (while jDarkroom does it for free).

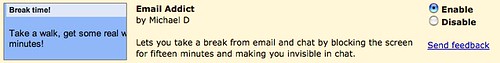

Riding the wave, Gmail just introduced a useful new feature, giving users the ability to shut down email for a while.

Image 2: Gmail’s Email Addict feature

Such features clearly minimise distractions such as blinking new-email notifiers. But they also help us minimize temptations, that is they help us control our future behaviour by hiding temptations.

The Power of Weakness 1: Choose your users with care, objects!

I’m immensely fascinated by the ways in which we, the alleged Homo Sapiens, set up our environments and construct our objects in order to make them difficult to navigate and use.

And I’m not being the least bit sarcastic here. We do, deliberately, and for excellent reasons, limit others and (even, more fascinatingly, ourselves) from easily taking certain causes of action in the future.

Now, this general topic is of profound depth and importance. We’ll discuss that another time then, shall we?

Today, let’s limit ourselves to a mere minor aspect of these big questions: Designed objects which, by their design, test and select their users.

The most common of such objects is the lock. The lock is an object which selects among the pool of possible users by being inoperable without the key. Thus, a lock requires the user to be in possession of a certain object.

Objects can test users in two other ways.

First, they can test for a certain knowledge. This is merely another type of lock, typically manifested as the need to know a password.

Second, an object can test for a certain characteristic (and here I use the term characteristic to also cover abilities).

Image 1: To open, you need to hold down the small white button, while first turning then sliding the lock to the left

An example of the latter is the child lock. The child lock is meant to impose minimal annoyance on the adult user wanting to open a window or a kitchen cupboard, while making it impossible (or very difficult) for a young child to operate it. A child lock typically tests for several characteristics: Physical strength, logical thinking, and dexterousness.

Image 2: To get onto this climbing wall, you need to be of a certain height

The alternative to child locks (in the broadest sense) is often complete inoperability (blocking the window until the child grows up) or posting a human evaluator/guard. The latter approach is The Amusement Park approach – amusement park rides often demand that users be of a certain height. But unless the guard is awake, anyone could get on board.

Now you’re entitled to your own aesthetics, but in my opinion the child lock approach is by far the more elegant. I think objects which cannot be used by users who shouldn’t are simply cool.

Of course, we can the discuss how this relates to things like the politics of artefacts if you’re interested…

Oh, a knowledge test is sometimes used to test for age… But it’s pretty inaccurate and often functions more like a test of whether the user can read and use Google.

Understanding Video Games now in stores

The video games text-book which I have co-written with Susana Tosca and Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen has now left the printers and reached the virtual shelves of Amazon.com.

The video games text-book which I have co-written with Susana Tosca and Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen has now left the printers and reached the virtual shelves of Amazon.com.

The book is so interesting that it actually has a (somewhat rudimentary) Companion Website featuring the book’s brief introduction chapter.

If you’re in Denmark, here’s a list of fine web book stores that will be happy to ship the book to you.

If you’re in the UK, you can get it directly from Routledge.

It’s 16.99 UK Pounds / 29.95 USD, took some time to write, and we do hope you buy it :-)

Going local for a while

Change is the spice of life, and instead of sporadically posting here I’ll be blogging in my mother tongue for a while over at teknokratiet.dk.

Change is the spice of life, and instead of sporadically posting here I’ll be blogging in my mother tongue for a while over at teknokratiet.dk.

If your Danish isn’t too rusty, you are warmly encouraged to participate.

…

Facebook is upon us

You may have noticed from that desperate plinking of your email client that Facebook is taking over the world. The invasion of Denmark started for real, relatively late, around October of this year.

I wrote a little analysis of the phenomenon for the newspaper Politiken a few weeks ago. If your Danish skills are up to it, you can read it.

The point, in essence, is that I see four main motivations for using Facebook:

1) Social necessity: You want to be where your friends are

2) Identity management: Being able to construct a self image, with great control and many options, is appealing

3) Worried curiosity: Who knows, something very important might be happening in there

4) Practical help: Keeping track of friends and weak ties through Facebook is simply practical

Of course, this list leaves out a factor: Hanging out on Facebook is simply entertaining (as Malouette mentions.). It is a constant cocktail party (although one with too little hard liqueur and too many zombies) and members of homo sapiens, as a rule, enjoy being social. Of course, to get all long-haired (and to protect my little list from criticism) one could argue that “fun” is a meta-factor. Using Facebook is “fun” because it satisfies “needs” such as the ones in my list.

Comments, questions and mad outbursts are welcome as always.

Facebook: Vi er blevet hypersociale

Analyse bragt i Politiken 18/11-2007

Af Jonas Heide Smith

Et bemærkelsesværdigt antal danskere tilmelder sig hver dag den sociale internettjeneste Facebook.

Tjenesten, der har over 50 millioner medlemmer på verdensplan, har på det seneste udvist vækstrater, der har sendt den til tops på oversigter over de største netværkstjenester i den vestlige verden. Men hvorfor er amerikanske Facebook så meget mere populær end de fleste konkurrenter? Og hvad er det i det hele taget, der i skrivende stund har motiveret, rundt regnet, 145.000 danskere til at tilmelde sig?

Lad os allerførst se på, hvordan tjenester som Facebook overhovedet fungerer. Typisk er de organiseret omkring brugernes profilsider, der i udgangspunktet indeholder brugerens grundlæggende demografiske data. Brugeren angiver, hvilke af systemets brugere vedkommende betragter som ’venner’, og knytter derved sin profil til disse venners profiler. Venner kan interagere med hinanden på flere måder. De kan skrive løst og fast på hinandens profilsider, publicere information om sig selv, som venner kan læse og kommentere, samt anvende særlige funktioner, der f.eks. tillader venner at spille små spil sammen, sammenligne filmsmag eller sende virtuelle gaver til hinanden.

Her er en vigtig ingrediens i Facebooks succesopskrift. Ved at åbne for, at andre virksomheder kan bygge små programmer, som Facebook-brugere frit kan forlyste sig med, har man åbnet for en kreativ gavebod af sjove, nyttige, tankevækkende og selvfølgelig til tider overflødige småtjenester, som brugerne kan boltre sig iblandt. Der er p.t. over 8.000 sådanne tilbud.

ET ANDET element i succesen er historisk. Facebook startede som en kommunikationsplatform for studerende ved Harvard College og udvidede kun gradvist til andre universiteter og siden til hele verden. Hermed fik man funktionaliteten på plads, mens man endnu havde en begrænset og velvillig brugergruppe, og man fik etableret en konstruktiv kultur på tjenesten, før man lukkede gud og hvermand indenfor. Idéen om at koble studerende fra samme årgang eller studium sammen er stadigvæk central på tjenesten og fungerer antageligt som indledende incitament for mange. Endelig tæller det naturligvis til Facebooks fordel, at man har kunnet lade sig inspirere af tidligere tjenester som Friendster og My-Space.

MEN HVAD ER DET SÅ, der får de ca. 145.000 danskere, og de 50 millioner andre brugere, til at skrive små beskeder på hinandens profiler og sende virtuelle drinks rundt i endeløse baner? Hvor får de tiden fra, og kunne de ikke bruge den bedre, f.eks. ved at læse bøger, lave lektier eller mødes på god gammeldags face to face-maner? Noget dybt og entydigt svar finder vi ikke i internetforskningen. Men der er formentlig tale om i hvert fald fire overordnede motivationstyper.

For det første er deltagelse for nogle ganske enkelt en forudsætning for at deltage i det sociale liv. Internetforskeren Danah Boyd nævner, at på spørgsmålet om, hvorfor de deltager på MySpace, svarer mange teenagere: »Fordi det er der, mine venner er«. Denne årsag kan vi kalde for ’social nødvendighed’.

En anden motivationsfaktor, der måske især er væsentlig for børn og unge, er muligheden for at eksperimentere med sin selvfremstilling. Man har på tjenester som Facebook og MySpace udstrakte muligheder for at fremstille sig selv, som man ønsker, og i øvrigt eksperimentere med social interaktion i relativt trygge omgivelser. Denne årsag til brug af tjenester som Facebook kan vi kalde ’identitetsudvikling’.

Den tredje forklaring er mere jordnær: Mange melder sig til af nysgerrighed. Mange danske brugere er tilmeldt Facebooks Danmark-netværk, og nogle placerer en kort besked på netværkets fælles opslagstavle. Et par af de nyeste lyder »Hvad sker der mon herinde.. :-)«, »Heya.. Nyt kød på markedet… HJÆÆÆLP…« og »Hejsa. Så er jeg også kommet her ind på Facebook.!! he he – Nu må vi se hva det bringer…«. Disse brugeres interesse er formentlig mestendels blevet vækket af den omfattende omtale i medierne. Der er tale om »bekymret nysgerrighed«.

Den fjerde forklaring er af samme banale kaliber, men bør ikke glemmes. Facebook fungerer som en dynamisk og levende telefonbog og hjælper brugere med at opretholde kontakt med hinanden på det ønskede niveau. Og tjenesten kan hjælpe med at organisere hverdagsaktiviteter blandt folk, der kender hinanden i forvejen. Her har vi at gøre med udsigt til ’praktisk hjælp’.

FLERE UNDERSØGELSER viser, at Facebook-brugere er langt mere optaget af at koble sig sammen med personer, de allerede kender, end af at møde fremmede. Så selv om det måske er mere interessant at tale om identitetsafprøvning, kan der faktisk være helt lavpraktiske årsager til at anvende sociale nettjenester. Dette faktum understreger noget meget centralt. Tror man, at Facebook-brugere forsømmer deres ’virkelige’ sociale liv til fordel for overfladisk placebo-interaktion, tager man grundigt fejl. Brugere af sociale nettjenester bygger, generelt set, et ekstra socialt lag oven på deres eksisterende forbindelser. De 130.000 danske Facebook-medlemmer konstruerer en social tillægsvirkelighed, der eksisterer parallelt – og med komplekse forbindelser – til den virkelighed, andre tager del i på arbejdspladser, i skoler og foreninger.

DER ER SÅLEDES ingen fare for, at sociale nettjenester fremelsker asociale karaktertræk og lokker folk til at flygte fra det sociale liv. Hvis man ønsker at bekymre sig, bør man måske snarere overveje, om det sociale liv ikke kan tage overhånd. Hvis man bruger al sin tid på at opbygge og pleje forbindelser og offentliggøre sine vurderinger af dette og hint, hvordan skal man så få de oplevelser og opnå den viden, som netværket netop kunne have glæde af? Spørg ikke mig, jeg skal ind og tjekke, om mine venner har fået nye venner.

Playful politics

A parliamentary election is almost upon is here in modest-sized Denmark. The current right-of-center government, supported by the nationalist Danish People’s Party, is being challenged by a left-of-center axis. With Christian Democrats unlikely to reach the (non-taxing) cut-off of 2% and our most left-wing party balancing on that same edge. Also, Helle Thorning-Schmidt – leader of the Social Democrats – could theoretically be the country’s first female prime minister.

Anyway, much has been said (not least in my course on Digital Rhetorics) about the esteemed candidates’ use of online media (for instance by knowledgeable colleague Lisbeth Klastrup). So let us instead focus on that less-dominant genre the political game.

We know how Howard Dean laid the foundations, and how former colleague Gonzalo Frasca helped the president of Uruguay (if we don’t know, we may want to read Ian Bogost’s recent book Persuasive Games).

In present day Denmark, however, political video games do not exactly overwhelm the politically curious citizen. But I have found a couple of specimens:

Overbudsbold: Made by a team of ITU students for DR. The player chooses a leader of a political party and an opponent to engage in a type of tennis in which the “ball” is a money bag growing bigger each time it is pushed over the net. The game comments on the tendency for candidates to attempt to top one another in promises. The idea, I believe, is that this practice is nothing but a silly game. Overbudsbold stands apart from the crowd in my opinion by being actually fun to play in its own right.

Så’ det ud: The youth branch of the Liberal party (in government) have published a game in which you (as current minister) place opposition leaders in a catapult and fling them as far as you can. No political statement is being made, to put it mildly. It’s slightly odd that the “heroes” are as caricatured as the opposition here, since no other attempts are being made at fairness.

Kampvalg is a game made by game developers Press Play. Here (as in Overbudsbold) two party leaders face of. But Press Play have exhanged Pong for Tekken in terms of inspiration. The player must attack the opponent using a small selection of aggressive moves.

Finally, ValgSpil ’07 is another developer showcase. Here you, as the player, must “survive a press meeting”, answering questions from reporters in an attempt to keep the general opinion on your side. The argument seems to be that party leaders face difficult a difficult challenge of presenting their policies without estranging voter groups.

In summary, only one game (“Så’ det ud”) with a political stance. The others hint/claim that politics is war – and, in the case of Overbudsbold, a rather silly exercise.

A somewhat underwhelming collection, perhaps. Did I leave out anything worthwhile?

Happy voting tomorrow, and may the best candidate obtain the highest score!